Spotlight on An Artist- Igor Mosiychuk Demo

Back in August, I got to watch Igor Mosiychuk do a live demo online, and I’ve been wanting to share about it ever since. For those who don’t remember, I did a post on Igor a few years ago, as part of my “Spotlight on an Artist” series-- you can read the post here. He’s a really stellar artist, and is well worth following on Facebook and Instagram, etc. It was a paid live stream for me, but they let me share screen shots— which is good news for all of you! ;)

Speaking of which— what an adventure to gain access! LOL. I saw he was doing a stream and touched base (using Google translate, of course), but because he’s in the Ukraine, there’s no access for things like Paypal, etc. Instead, for the first time ever, I had to use Western Union to send payment. Now, I know I’m dating myself by saying this (a little younger than some, and a little older than others), but I’ve never used it before. I didn’t realize it’s like the original Paypal! :D Thank goodness they’re still around in grocery stores and such.

So, I like watching things live— there’s an energy to things happening in real time that I appreciate more than a recording. As such, I got up at 300 in the morning on a Tuesday (?), and shlumped down in front of my computer, waiting for things to get rolling. Luckily, it was a beautiful morning full of chatty students in the Ukraine! It really is an amazing time we live in. What a privilege to get to see him paint, live, from my office. Ok, on to the demo!

First things first, Igor paints flat, and (once he’s finished his sketch) he starts by wetting the front and back. You can see that in these first two pics. He used a big hake to wet the paper down and then lift off any excess water. So, this is really different from someone like Joseph Zbukvic, who tapes his paper down dry, paints with a tilt, and uses a bead. It’s neat to see two really excellent artists use the medium in really different ways.

1

2

Once the paper was wet, there was a long pause. Almost half an hour. During this time, he showed us his brushes and his palette, and was generally chatty. Of course, this was all in Ukranian (?). I know a little Russian, but this was all way over my head. Still, what became clear as I watched him is that he actually uses a lot of flats, which surprised me. This became important later on, because they provided him a way to regulate the volume of water on his paper. Flats don’t carry as much water as a mop, but cover more space than a synthetic round. Since he’s painting wet-into-wet for much of the process, this “water regulation process” is extra important.

3

4

His palette was large, and looked like a Holbein. My apologies, but I didn’t keep track of which pigments he used. I admit, this is not usually a very important detail to me, unless the artist is deliberately using a specialty pigment for certain effects.

After a little break, he came back to the paper with a large hake, and got to work on the clouds. Something to note is that a) the mix in his palette is not super wet and puddly, and b) the clouds are not super wet, and are not running everywhere. The paper itself is already wet, so he doesn’t need to have his brush or paint mixture deliver a lot of extra moisture. His brushes are, relatively speaking, dry.

5

6

In Pic 6, you can see him using a tissue to daub off an area. He did this to sometimes lift paint, and sometimes to prep a blank area for a brushstroke, allowing him a hard edge or drybrush work.

For the darker, smaller clouds, he shifted to a smaller brush. Note how dry this brush is too. He’s flattened it a bit, and you can see the bristles stay separated. It’s wet, but not so soggy it’s coming to a point. In Pic 8, you can actually see that the bristles are tilted— a sure sign that the brush is wet, but not saturated, because it’s holding its form.

7

8

After that, it’s back to the tissue. This lets him work on the faraway mountains without it dripping anywhere. You’ll also see in Pic 9, that he’s prepping for future details in that area. Beyond that, he also shifts to an even smaller flat. This lets him apply a darker mix more easily- the edges are a little tighter, the mixture has less water on the brush, etc etc.

9

10

In the next two stillshots, two big things have happened. One is that he’s painted the fences. This is part of why he was daubing things off with the tissue earlier. It lets him have hard edges. But you also have to remember that he let the paper sit for 20-30 minutes before starting to paint, and second, he’s been painting for atleast 30 minutes or so by now. So, the surface of the lower half of the paper is actually dry-ish by the time he reaches it. Because of that, he actually quickly rewet the bottom of the paper (after painting the fence posts) to get soft edges again. After that, it’s quick work to block in what will become the grass.

11

12

In Pic 12, he’s still using the smaller synthetic flat. You can see he’s dropped in some texture on the foreground grass, which he did with this brush. Note how he’s able to keep hard edges for that path on the left. This is just done with planning and timing— he either didn’t rewet that area specifically, or he daubed it off with a tissue. The other thing he did was sprinkle in water with this short-haired brush, by flicking the bristles with this finger. This kind of method better lets him aim the droplets where we wants— down onto the grassy area. And with this, he was done with Phase 2. You’ll see where the droplets landed in the next pics, after they’ve had time to expand.

13

14

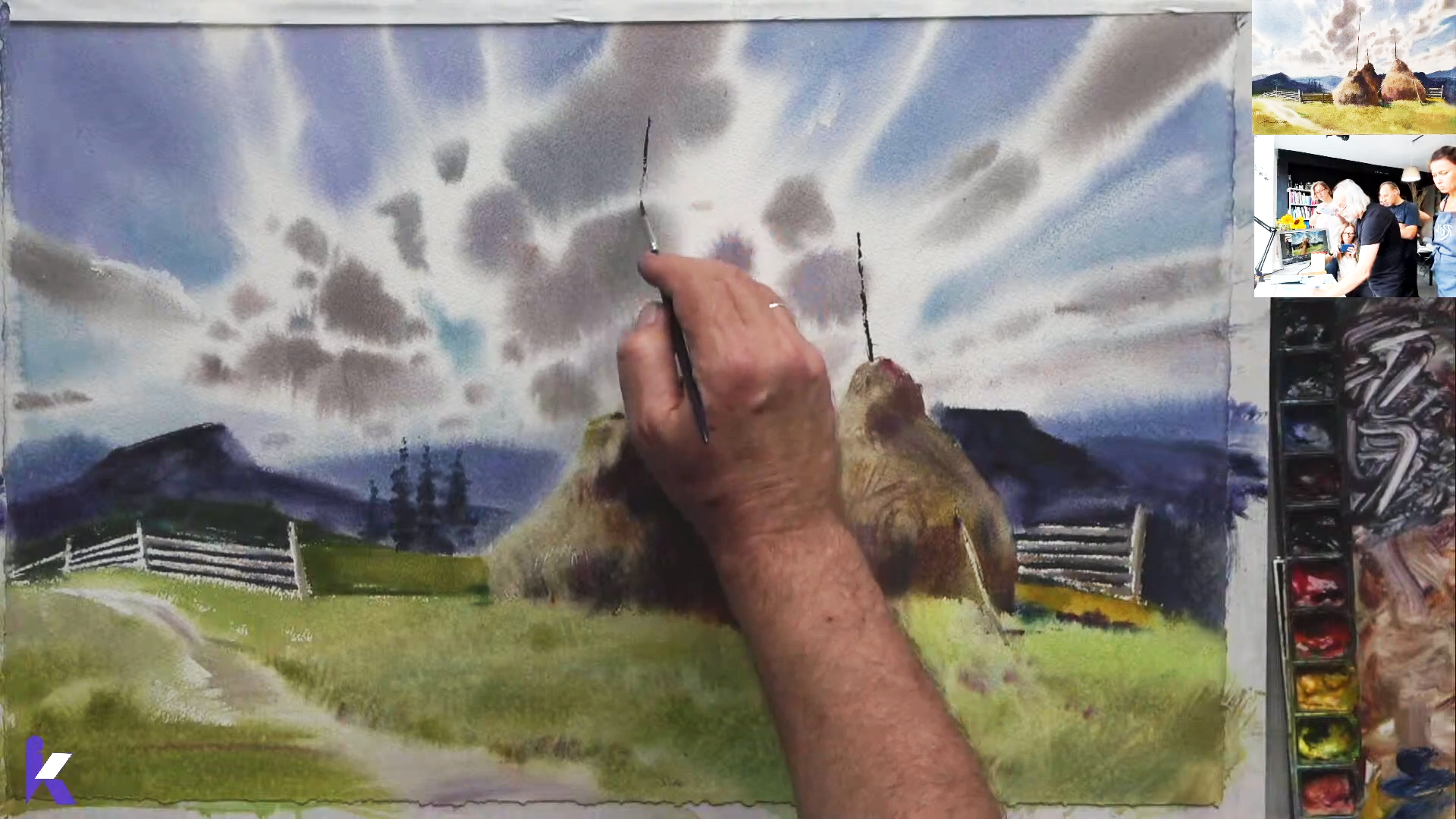

After a 20 minute break, Igor came back and got to work. The first thing he did was gently pre-wet the focal point (the two haystacks). But not the whole area! He was very clear about doing it judiciously, so he could keep hard edges where he wanted. Then, he dove in with a small flat hake, to drop in the pale brown base color.

The big shift, for me, in this final section is that Igor changes his hues when putting in the focal point. Of course, the haystacks actually are warm, and sky and distant mountains maybe really were blue, but it’s hard to say what reality was like. Part of being an artist is being aware of when the natural world creates contrast-relationships that are compelling— contrast-relationships, hue relationships, etc. But part of it is, as I see it, also shifting things as needed, to tell the most compelling story, emotionally. Sometimes, as an artist, “you have to lie to tell the truth”. So, I doubt things were as blue and purple as they are in the painting, and I doubt that gorgeous red seam inbetween the haystacks was as vibrant as it is in his painting. But these color relationships are part of what make the painting dynamic.

15

16

I also got a kick out of this final phase because he started to use an assortment of different tools. In Pic 15, for example, he’s using a razor or a sharp metal “pick” to scrape out tiny highlights. This reminds me of how I’ve seen other watercolorists use the edge of a metal palette knife (Chien Chung Wei) or the edge of the cap of watercolor paint (Bjorn Bernstrom) to create highlights for wires. Then, in Pic 16, now that things are drier, he goes in and knocks back the whites on the fences, doing a bit of grey drybrush work on them.

Next up are these poles that drop into the stacks. I don’t know what they’re for. Perhaps if you do, you can share in the comments? Something he did for this, what I thought was neat, was that he used a small rigger and laid it flat and actually sort of daubed in the lines. So, he wasn’t dragging the brush, the way you normally would, but was “laying the brush down” piece by piece. This allowed for interesting texture, and a lot of control.

17

18

And then finally, the finished piece. The whole thing took about 2 and 1/2 hours. Long for a demo, by US standards, but very normal, in my opinion, for a typical painting process for a 1/2 sheet size. What a joy!

Thanks Igor! :) It was a pleasure watching you paint. Folks really should follow him on Facebook and Instagram.